Asylum-seekers stuck in Cyprus’ cramped camp want out

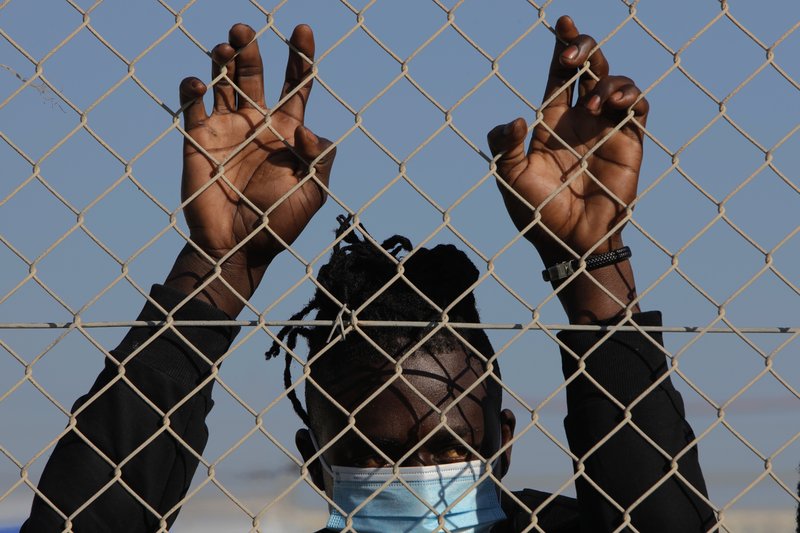

A migrant wearing a face mask stands behind a fence inside a refugee camp in Kokkinotrimithia outside of capital Nicosia, Cyprus, Friday, Feb. 5, 2021. Cyprus’ Interior Minister Nicos Nouris said this week that the east Mediterranean island nation whose closest point to Syria is around 150 kilometers (93 miles) remains first among all other European Union member states with the most asylum applications relative to its population. Last year, the country of around 1.1 million people racked up 7,000 asylum applications – most of them from Syrians (AP Photo/Petros Karadjias)

NICOSIA, Cyprus (AP) — Emmanuel Conteh negotiates the muddy, rutted pathways in shorts and torn plastic flip-flops and says he can’t sleep in his heavy canvas tent at night because of the cold.

He laments the “hellish” conditions in ethnically divided Cyprus’ cramped Pournara migrant reception camp, where he’s been living for the past two months after flying to the breakaway Turkish Cypriot north and then clandestinely crossing into the internationally recognized south.

He says he fled his native Sierra Leone because he was persecuted for refusing to follow in his father’s footsteps and practice a kind of witchcraft.

“The head of this society, they want to train me, but I refused,” said Conteh.

He wants Cypriot authorities to swiftly process his asylum application and let him and others out of the razor-wire-encircled former military camp near the industrial western fringes of the capital Nicosia that he says feels like prison.

“We’re not prisoners. We’re asylum-seekers. Let them finish our process and then (free) us,” Conteh said. “That’s all we’re asking.”

The small eastern Mediterranean island republic is trying to cope with a huge backlog of asylum applications and despite government efforts to expedite the process, migrants say they feel literally left out in the cold.

Designed to accommodate 1,000 people at the most, Pournara is a “first instance” camp where in theory asylum-seekers are initially processed and released after three days. But it now houses 1,500 people, some of whom have been there for months.

Interior Minister Nicos Nouris said this week that Cyprus remains first among all other European Union member states in asylum applications relative to its population.

Last year, the country of around 1.1 million racked up 7,000 asylum applications — most of them from Syrians. Nouris said the government is doing its best to speed up the application process to let in those who qualify and to send back migrants whose application is turned down.

Like Conteh, most asylum-seekers enter the island from the Turkish Cypriot north and cross a porous, United Nations-controlled buffer zone into the south. Many hope to transfer to another EU country on the continent.

But asylum-seekers say the process is just taking too long amid a slow-down in application processing brought on by COVID-19 restrictions. They insist that they’ve tested negative numerous times for the coronavirus and want authorities to open the camp’s gates so they can seek better accommodation.

He claimed that authorities are favoring Syrians, letting them out of the camp sooner and more frequently than Africans.

That frustration boiled over earlier this week when African migrants tried in protest to block Syrians from exiting.

Cypriot government officials deny there’s any discrimination regarding the timing of migrants’ release. Interior Ministry spokesman Loizos Michael said releases must be done gradually and in order of priority, starting with women, children and minors.

He said a daily stream of arrivals to the camp is making conditions tougher on those living there, but camp authorities are making “herculean efforts” to improve the situation.

But Corina Droushiotou who heads the Cyprus Refugee Council — a group that offers legal help to migrants with their asylum applications — said the migrants’ “de facto detention” at Pournara is “completely unnecessary” and is fanning anger among the migrants, some of whom have been living there for as many as five months.

Droushiotou said despite continued, island-wide COVID-19 restrictions including a night-time curfew, authorities could have eased tensions by allowing people who found a place to stay outside the camp to leave. Others could have been permitted to leave for short periods on condition they return before the start of curfew.

“The situation in Pournara signals a failure by the authorities to effectively address ongoing issues related to migrants and refugees,” said Droushiotou, adding that the government lacks a comprehensive migration and integration strategy.

— Associated Press